(This item was posted yesterday. Some readers felt it may have been overlooked, as it was a Sunday, and have asked us to repost it)

(This item was posted yesterday. Some readers felt it may have been overlooked, as it was a Sunday, and have asked us to repost it)

You might recall last week’s post concerning Dr Julien Mercille (top), of University College Dublin and his report into the Irish media and the property bubble.

His academic paper claims that organisations such as the Irish Times, The Independent group and RTE helped stoke, sustain – and ultimately fail to warn people about the dangers of – the bubble.

Having now read the report.

It wasn’t all bad news..

Dr Mercille (who has given us permission to quote from his findings), writes:

“In Ireland, economist David McWilliams (centre) warned unambiguously about the unsustainability of the boom as early as January 1998, when he wrote that ‘fundamentals count for nothing if your house is built on a bubble’ and pointed to the fact that mortgage lending in Ireland ‘has been growing at 15 per cent per annum for the past four years. This cash has been funnelled with the help of significant fiscal incentives, into bricks and mortar, pushing, as we all know, prices through the roof. On top of this, general credit in the economy is up more than 20 per cent in 1997 alone. A quick glance at property prices suggests that we are definitely entering asset-price bubble territory’. Until the crash, McWilliams has been one of the few analysts in Ireland to warn publicly and explicitly about the growing housing bubble and its eventual collapse. Another Irish analyst to have done so is Morgan Kelly (above). He looked at nearly 40 property booms and busts in OECD economies since 1970 and showed that there is a strong relationship between the size of the boom and ensuing bust: typically, ‘real house prices give up 70 per cent of what they gained in a boom during the bust that follows.”

“Kelly observed that, between 2000 and 2006,house prices in Ireland had doubled relative to rents, while the price-to-income ratio had also significantly outpaced its historical level. This showed that Irish property prices were no longer sustained by fundamentals such as rising employment, immigration or rising income. He predicted a fall in real house prices of ‘40 to 60 per cent over a period of 8 to 9 years’, which seems relatively accurate as of this writing.”

But.

The prevailing mood was such that:

“Marc Coleman, the Irish Times economics editor, wrote as late as September 2007 that: ‘Far from an economic storm – or a property shock – Ireland’s economy is set to rock and roll into the century’. In fact, ‘Ireland enters the 21st Century in a position of awesome power’.

[Of Brendan O’Connor’s June, 2007 Sunday Independent column: ‘The Smart, Ballsy Guys Are Buying Up Property Right Now’] “(The article was) urging Ireland’s readers to buy property, saying himself: ‘Tell you what, I think I know what I’d be doing if I had money, and if I wasn’t already massively over-exposed to the property market by virtue of owning a reasonable home. I’d be buying property. In fact, I might do it anyway…anyone who is out there in the jungle will tell you that it is a buyer’s market big time’

Dr Mercille gives four reasons why the media may have sought to downplay the bubble and its dangers.

1) The news organisations have multiple links with political and corporate establishment, of which they are part, thus sharing similar interests and viewpoints.

2) Just ‘like elite circles’, they hold a ‘neo-liberal ideology’, dominant during the boom years.

3) They feel pressures from advertisers, in particular, real estate companies.

4) They rely heavily on ‘experts’ from ‘elite institutions’ in reporting events.

He writes

“Irish news organisations are large private or government-owned institutions, and as such are themselves part of the corporate and political establishment…”

“…The overall point is that news content reflects economic and political elites’ interests and views. The Irish media can be seen as neoliberalised, in line with Ireland’s political economy. Over the last several decades, mergers have reduced the number of smaller, independent regional news organisations and increased the concentration of ownership, while the liberalisation of the industry has allowed a number of foreign companies to take stakes in the Irish media. It has been argued that increased commercialisation has contributed to a shift away from investigative journalism and toward a ‘tabloidisation’ of the news.”

Dr Mercille says because the property boom helped key sectors of the Irish corporate and political establishment, “it was never seriously challenged”.

“Government-owned media are by definition controlled by the government to a greater or lesser extent, through funding and appointments of principal officers. In theory, state-owned media could be more representative of popular concerns than private media since they are part of the democratic structure of government. However, this only goes so far as the government is democratic and, in Ireland as elsewhere, national politics are largely dominated by a few parties representing various factions of the establishment.”

“In 2008, PricewaterhouseCoopers conducted a detailed study offering a comprehensive look at the ownership, size and concentration of the media in Ireland that illustrates the above statements. Independent News & Media (INM) is arguably the dominant media conglomerate and is listed on the Irish and London stock exchanges. During the housing bubble years, it generated annual revenues of €1.67 billion (2007 data), owned 200 newspapers and magazines, 130 radio stations and 100 online sites in Ireland, the UK, South Africa, India, Australia and New Zealand. In Ireland, it owns seven national and 17 local newspapers and 27 websites. Some of those are leading titles, such as the Irish Independent, Sunday Independent, Sunday World and Irish Daily Star.

“Its main bankers are Bank of Ireland, AIB and Ulster Bank Ireland, which were all deeply involved in the housing bubble. Its board members and directors are establishment figures, including the financial sector. For example, board members have included Brian Hillery, a Director of the Central Bank of Ireland and former Fianna Fail member of parliament, Dermot Gleeson, the chairman of AIB during the housing bubble years, and B.E. Summers, a director of AIB.”

“The Irish media even acquired a direct financial interest in the sustenance of the real estate bubble by acquiring property websites. For example, in 2006, INM bought PropertyNews.com (along with the PropertyNews monthly newspaper), the ‘largest internet property site on the island of Ireland’ listing ‘nearly 20,000 properties for sale’. In 2006, the Irish Times, Ireland’s newspaper of record, also bought the property website MyHome.ie for €50 million, along with the website newaddress.ie which aims to make it easier for home owners to move residences. The Irish Times’ board has also been replete with individuals linked to the corporate and political establishment. For example, during the bubble years, the board included David Went, CEO of Irish Life & Permanent, an Irish bank deeply involved in the housing boom.”

“RTÉ is Ireland’s state-owned media organisation and dominates the television sector. It is funded through advertising revenues, indicating an important commercial dimension, and also by the government through license fees collected from the public. The government appoints RTÉ’s board, giving it additional influence on the organisation.”

“During the boom years, RTÉ had as chairman Patrick J. Wright, who was at the same time a director of Anglo Irish Bank, which epitomised more than any other bank the excesses of the Celtic Tiger and property lending. In 2006, Mary Finan took over as chair, with a resume including positions such as director of the ICS Building Society, a Bank of Ireland subsidiary mortgage lender that offered 100 per cent mortgages from 2005 onwards and was eventually covered by the 2008 government guarantee.”

In relation to advertising, Dr Mercille writes:

“The Irish media received a large amount of funding from property advertising during the housing boom (and, as seen above, they even became owners of property websites). Most newspapers published weekly supplements for commercial and residential property, ‘glamorizing the whole sector’, while ‘Glowing editorial pieces about a new housing estate were often miraculously accompanied by a large advertisement plugging the same estate’, in the words of Shane Ross, former Sunday Independent business editor.

“Ross also shows the power of advertisers’ in influencing news content when he states that: ‘Unfavorable coverage of developers and auctioneers in other parts of the newspapers was regularly met by implied threats from property interests that advertising could go elsewhere’.

“Moreover, a journalist working for the Irish media stated that journalists ‘were leaned on by their organisations not to talk down the banks [and the] property market because those organisations have a heavy reliance on property advertising’. As Irish Times columnist Fintan O’Toole remarked: ‘There is no question that almost all of the Irish media for the last 10–15 years has had a crucial economic stake in a rising property market. Because property advertising is very lucrative and is a very important part of what makes the Irish media tick’.“

Noting previous research [by Declan Fahy, Mark O’Brien,Valerio Poti, who interviewed Irish journalists about their work practices], Dr Mercille writes:

“One said that because of the need for regular contact and interaction with financial sources, ‘some journalists are reluctant to be critical of companies because they fear they will not get information or access in the future’. Another said that ‘many developers and bankers limited access to such an extent that it became seen to be better to write soft stories about them than to lose access. Extremely soft stories would be run to gain access’ to them as well. Threats of legal action limited the possibility of undertaking investigative financial reporting because banks and real estate companies could easily drag news organisations into expensive legal procedures, so that ‘Very often a threat of an injunction is enough to have a story pulled’, while many legal actions by powerful individuals or corporations are ‘executed purely to stifle genuine inquiry’.

“One journalist even mentioned that reporters face much pressure from the industry to influence news content, and that it is ‘well known that some PR companies try to bully journalists by cutting off access or excluding journalists from briefings’. The next section confirms empirically that property ‘experts’ from institutions like banks and the real estate industry were often interviewed by Irish journalists during the bubble years, with the result that their views dominated the news.”

In relation to post-boom coverage by the Irish Times, the Irish Independent, the Sunday Independent and RTÉ, Dr Mercille adds:

“The first point to emphasise is the clear discrepancy between coverage of the housing bubble before and after it burst. Before 2008, the media tended to largely ignore the growing property bubble and it is only months after it had burst that discussion of the subject became more prevalent. Once the housing market collapsed, the media simply could not ignore its downward trajectory, hence the increased coverage. This again reflected the views of political and economic elites, who eventually had to face reality, let alone because Ireland’s creditors would soon ask to be paid back.”

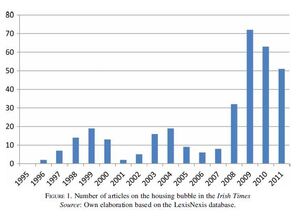

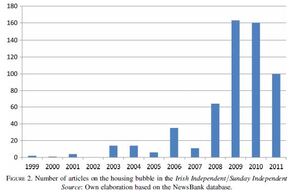

“Figures 1 and 2 show the number of articles on the housing bubble that have appeared in newspapers by year.1 The methodology used to construct those graphs consisted in identifying articles that discussed the housing bubble in Ireland. The keywords used were ‘housing bubble’, ‘property bubble’ and ‘real estate bubble’. These terms were judged to be the most appropriate ones to assess media emphasis and neglect of the Irish housing bubble. Other terms such as ‘housing boom’ or ‘housing affordability’ would have returned articles on related subjects, but would not necessarily have denoted coverage of a housing bubble, which by definition refers to abnormally inflated housing prices. For example, the phrase ‘housing boom’ has positive connotations and was often used in the media before the crash to give overly optimistic assessments of the property market.

“Similarly, there have been news stories about corruption in the planning and political systems as related to housing, but those only rarely considered the fact that, at a macro level, the property market was in bubble territory. On average, the Irish Times had 5.5 times more articles on the bubble per year in 2008–11 than in 1996–2007. Similarly, the Irish Independent/Sunday Independent had on average 12.5 times more such articles in 2008–11 than in 1999–2007.3 Moreover, the few articles published during the earlier period often denied that there was a bubble. For example, Irish Times articles’ titles included: ‘Irish Property Market Has Strong Foundations’ (29 October 1999), ‘Study Refutes Any House Price “Bubble”’ (18 November 1999), ‘Bricks and Mortar Unlikely to Lose Their Value’ (11 December 2002), ‘Prices to Rise as Equilibrium is Miles Away’ (18 March 2004), ‘House Prices “Set for Soft Landing”’ (22 November 2005), ‘Property Market Unlikely to Collapse, Says Danske Chief’ (2 February 2006) and ‘House Prices Rising at Triple Last Year’s Rate’ (29 June 2006). The Irish Independent/Sunday Independent reveal the same pattern, with headlines such as: ‘NCB [Stockbrokers] Rejects House Value Threat from Burst Bubble’ (11 February 1999), ‘Property “Bubble” is Not Yet Ready to Burst’ (23 April 2003), ‘The Property Bubble Never Looked Like Bursting in County Roscommon’ (16 May 2003), ‘House Prices Not About to Fall Soon, Insist Auctioneers’ (1 June 2003), ‘Dire Predictions of Collapse in Value of Homes Dismissed’ (5 October 2003), ‘Price of Houses “Not Over-valued” Says New Report’ (19 December 2003), ‘There is no Property Bubble to Burst, Despite Doomsayers’ (27 June 2005), ‘Influx of Workers Gives Big Boost to Property’ (25 January 2006) and ‘Property “Bubble” Could Continue Expanding’ (10 February 2006).

“Of course, there were some articles warning about the bubble, such as David McWilliams’ (1998) piece and those by Morgan Kelly. However, such warnings were effectively drowned in a sea of articles either denying there was a bubble, remaining vague about it or simply talking about something else. For instance, between 2000 and 2007, the Irish Times published more than 40,000 articles about the economy – but only 78 were about the property bubble, or 0.2 per cent.4 This is small coverage for what was arguably the most important economic story during those years. Articles that cautioned against the possible negative repercussions of a real estate bubble were often met with stories throwing doubts on such claims or arguing that things would be fine. For example, in 2003, an Irish Times article dampened possible worries of an overvalued property market with a story entitled ‘IMF Points to “Significant Risk” of Overvaluation on House Prices; The Irish Property Market May Be in “Bubble Territory”. Or Then Again Maybe It’s Not. Even the IMF Can’t Make Up its Mind’.

“The media relied on so-called ‘experts’ from the financial or real estate industry to describe the market, which thus received almost invariably upbeat analysis. For example, as late as November 2007, the Irish Times conducted a survey among ‘property experts’ to predict how the market would evolve in 2008. The six experts selected all held high-level positions with property firms:

Managing Director, CBRE (global commercial real estate services firm)

Investments Director, Lisney (leading Irish real estate agency)

Managing Director, Savills HOK (global real estate services provider)

Managing Director, Sherry FitzGerald (leading Irish real estate agency)

Managing Director, Ballymore (Irish property company)

Chief Executive, IPUT (largest property trust in Ireland)

Director, Finnegan Menton (Irish property consultancy firm).”“Not surprisingly, their forecast was enthusiastic. Their responses included statements such as: ‘We have an underlying economy which by any standards is good’; ‘The good times are not over’; ‘There is a lot of cash out there looking for safe homes in an economy that is continuing to grow’; with ‘capital values likely to bounce back during the course of the year, the timing is right to buy development land to catch the upswing for residential development’; ‘The broad macro economic fundamentals of the Irish economy are sound’; ‘we are in a cooling off period and not a collapse’; and ‘the commercial investment market will provide solid positive performance’.

“The views of experts were also used directly to discredit suggestions that the market was overheating. For example, an article entitled ‘Study Refutes Any House Price “Bubble”’ started with the following sentences: ‘There is no house price bubble, according to Mr Jim O’Leary, chief economist at Davy Stockbrokers. In the latest report on the housing market, Solid Foundations, Mr O’Leary said the market has been driven by fundamental factors and these would need to reverse for the market to collapse’.”

“The residential and commercial property sections and supplements also contributed articles and glossy pictures encouraging readers to get into the real estate market. Such articles described various properties on sale and were virtually indistinguishable from advertisements. For example, one entitled ‘There’s a Billion Reasons to Buy’ presented a new development of luxury apartments noting that the ‘extra spacious apartments feature quality designer kitchens with integrated AEG appliances and stone worktops; top notch bathrooms with ceramic tiles, heated towel rails and chrome fittings; recessed lighting and centralised heating’. It continued by assuring the reader that such a ‘high spec naturally positions this development at the upper end of Dublin’s residential market and it is set to become a benchmark for the capital’. Potential buyers should waste no time:

‘However you don’t have to be a millionaire to buy into such billion euro territory – 355,000 is all it takes to stake your claim. But numbers are strictly limited – you’d want to stake it fast’.”

…

“Journalists persisted in rejecting the view that the Irish property market had been in a bubble months after it started collapsing. A few examples have already been given above of articles published in mid to late 2007 still claiming that the housing sector would either continue to go up or that a soft landing was the worst that could be expected. Other similar stories appeared in 2008, such as the following: ‘The faint-hearted agonise over buying, hoping that prices will fall further. But don’t wait. Buy now, don’t listen to the doomsayers’“Television followed the same pattern as the print press. During the boom, RTÉ sustained the national obsession with houses by presenting programmes like House Hunters in the Sun, Showhouse, About the House and I’m an Adult, Get Me Out of Here.

…[RTE’s] Prime Time…Between 2000 and 2007, had a total of 717 shows aired, according to RTÉ’s website. Of those, only 10, or about 1 per cent of the total, had a segment concerned with the housing boom. These presented a total of 26 guests or interviewees: 11 came from the property or financial sectors (banking, insurance or stockbrokers); four were politicians from Ireland’s establishment political parties (Fianna Fail, Fine Gael and Labour); four were journalists; four were academics or researchers; and three were economic consultants. With respect to their views on the housing boom, only two (David McWilliams and Morgan Kelly) stated clearly that there was indeed a bubble and that it would burst. The 24 others remained either vague or argued explicitly that the housing market was and would remain strong in the years to come, or that a soft landing was to be

expected if the boom decelerated at some point.“For example, economic consultant Peter Bacon said that the ‘housing market is well underpinned by demographics’ (27 August 2003). Fianna Fail politician Sean Fleming declared that ‘definitely, the house market is going to be very strong in Ireland for the years to come’ because of ‘growing population’ and because ‘incomes are strong’ (12 April 2006). On the same show, Shane Daly (of real estate company Gunne New Homes) said that ‘people exaggerate often the level of debt that people are getting into’. A few months later, on 18 October 2006, Marian Finnegan (of real estate company Sherry Fitzgerald) said that ‘we are looking at a soft landing’. As late as 6 June 2007, Eunan King (of NCB Stockbrokers) stated that there won’t be a crash. It was only in April 2008 that Prime Time seemed to acknowledge as fact the sharp drop in housing prices.

“In April 2007, RTÉ aired a one-hour programme entitled Future Shock: Property Crash, which outlined some of the possible dangers of a drastic decrease in house prices. Even though it came several years after The Economist had clearly presented the fact that Ireland was in a housing bubble, it still generated vigorous counterattacks in the Irish media. Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern denounced its maker, Richard Curran, as ‘irresponsible’ on the radio. The Construction Industry Federation, representing Ireland’s builders, said that the programme was politically motivated.

“Cliodhna O’Donoghue, the Irish Independent’s property editor, wrote that: ‘Future Shock was very much a shock tactics programme and many within the property and construction industry have already labelled it irresponsible, partly inaccurate and wholly sensationalist…the programme still did much damage to market confidence’. Marc Coleman asked, ‘why does RTÉ want to run down our economy?’ by presenting the programme by Curran, who is a ‘careless talker’. It is true that the programme offered a more critical perspective than much of the previous news coverage. However, when one considers that it aired just as the housing bubble started deflating, it cannot be taken as an example of a media that offered clear warnings of a bubble that had been growing for over a decade.”

Dr Mercille concludes:

“The overall argument is that the Irish media are part and parcel of the political and corporate establishment, and as such the news they convey tend to reflect those sectors’ interests and views. In particular, the Celtic Tiger years involved the financialisation of the economy and a large property bubble, all of it wrapped in an implicit neoliberal ideology. The media, embedded within this particular political economy and itself a constitutive element of it, thus mostly presented stories sustaining it. In particular, news organisations acquired direct stakes in an inflated real estate market by purchasing property websites and receiving vital advertising revenue from the real estate sector. Moreover, a number of their board members were current or former high officials in the finance industry and government, including banks deeply involved in the bubble’s expansion.”

Julien Mercille is a lecturer in US foreign policy at UCD, where he moved after obtaining his PhD from UCLA. He teaches on US history and foreign policy and has published academic articles on Iran, Iraq and the Cold War, and is now researching the “War on Drugs” and Afghanistan.

Previously: The Why

Pics: UCD/ David McWilliams, Jonas Fredwall Karlsso (Vanity Fair)