From top: WWN logo, Dustin the Turkey, Denis O’Brien, Solicitor Sarah Kieran

Further to [REDACTED]’s legal threat against satirical website, Waterford Whispers News…

Solicitor Sarah Kieran, of Media Lawyer Solicitors – who previously worked as a media lawyer at RTÉ for six years – spoke with Rachael English on RTÉ One’s Morning Ireland earlier about why she believes humour is little defence in a libel action.

Legal Coffee Drinker, meanwhile, offers a competing view (below).

Rachael English: “Talk to us, if you would, about the process of publishing or broadcasting satirical material in this country because it is a highly legalled process or, certainly, it can be.”

Sarah Kieran: “Yeah, absolutely. I think the first thing to say is that there’s no absolute right to freedom of speech in this country because you also have a right to your good name, under our constitution. And so this is where the difficulty arises. There is no such thing as an ‘only kidding’ defence or that ‘I was messing’. And the intention of the publisher, which is the person who publishes the piece, in this case, Waterford Whispers, it doesn’t matter what their intention was, the law will automatically deem that they have to prove what they said was correct.

So it is a very fraught process. And I think a lot of cases, it comes down to personal appetite. Some individuals are very protective of their reputations, as you can see in this instance and others take the view that any publicity is good publicity so I think for writers of satire they have to try and… it’s a very fine line so they have to try to get over it. And it depends on the personal appetite, as I said already, so. In this country, it’s a small country. We know high-profile people and what their views are so you will find that the writers of comedy sketches will know these individuals and you just have to make sure that you make it so good and so obvious that it’s satire, I think, to get it over the bar.”

English: “In general terms, what sort of advice would you give to a website, a radio programme, a newspaper columnist or whatever, who’s involved in satire.”

Kieran: “Well, just be conscious that there is no such thing as an ‘only kidding’ defence. Take high-profile subjects who are used to being, I don’t want to use the word ‘slagged off’ but the butt of satire, if you like. Make sure that it’s so surreal that it couldn’t be true, be very incisive of what you say and I think probably one of the most important things is the WAG factor, what we refer to as the WAG factor – leave the wives and girlfriends alone. And then there’s other issues like, for example, if you look at what Dustin the Turkey used to say about Pat Kenny and Anne Doyle and you have to consider, well how would they look if they had sued a turkey. So you have all of those considerations to take and consider…”

English: “I noticed actually, Dustin the Turkey was tweeting about this particular case but I better not say anything for fear I get into trouble myself. I suppose the other thing is that this case is also a reminder that defamation law, the defamation laws they don’t just apply to the papers or the radio. Writing something online can get you a solicitor’s letter.”

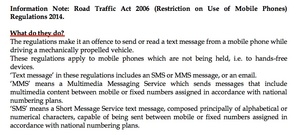

Kieran: “Absolutely and I think it’s something we all forget about because of the immediacy of what we do on social media these days. You know we post something on Facebook, we retweet a tweet, that’s a publication, that’s considered a publication under the law. So, in that instance, you can be liable for what’s been said and a lot of the time on social media like that cases are not necessarily brought because considerations are taken into account of, the influence of the person that maybe retweeted, or tweeting but there are cases, and there have been cases in this jurisdiction, there have been cases in the UK as well and it’s just the immediacy, I think we forget. It’s so easy just to post something so quickly on social media. And websites – the same liability applies as somebody who’s writing an article in the newspaper or taking part in a radio interview as I am now.”

Listen back in full here

HOWEVER…

Does defamation law really not recognise a sense of humour?

We asked Legal Coffee Drinker, what’s it all about.

Broadsheet: “Legal Coffee Drinker, what’s it all about?”

Legal Coffee Drinker: “Speaking technically, a ‘defence’ in legal terms arises where someone has committed a wrong, but has a lawful excuse for doing so. It’s true that in that sense, there’s no ‘only kidding’ defence for satirists; if they’ve committed defamation, they can’t say they were ‘only kidding’.

However, anyone suing for defamation must show that the ingredients of the wrong of defamation have been satisfied in the first place. Under the Defamation Act 2009, these requirements are quite clear. In particular, the person suing must show that the statement is defamatory – defined by Section 1 of the Act as a statement that tends to injure that person’s reputation in the eyes of reasonable members of society,

In deciding whether or not a statement is defamatory, context is key. The court will look not only at the literal words of the statement, but also its location. A factual statement made on a website which is clearly satirical in nature, will not necessarily be defamatory. The question is whether reasonable members of society would take the statement seriously, given its location.”

Broadsheet: “Any cases on this?”

LCD: Yes. This very issue came up in the U.K. in Sir Elton John v Guardian News & Media, [2008] in which Sir Elton John sued the Guardian in respect of the following satirical piece on his charity endeavours.

A PEEK AT THE DIARY OF…Sir Elton John

What a few days it’s been. First I sang Happy Birthday to my dear, dear friend Nelson Mandela – I like to think I’m one of the few people privileged enough to call him Madiba – at a party specially organised to provide white celebrities with a chance to be photographed cuddling him, wearing that patronisingly awestruck smile they all have. It says: “I love you, you adorable, apartheid-fighting teddy bear.”

The next night I welcomed the exact same crowd to my place for my annual White Tie & Tiaras ball. Lulu, Kelly Osbourne, Agyness Deyn, Richard Desmond, Liz Hurley, Bill Clinton – I met most of them 10 minutes ago, but we have something very special and magical in common: we’re all members of the entertainment industry. You can’t manufacture a connection like that.

Naturally, everyone could afford just to hand over the money if they gave that much of a toss about Aids research – as could the sponsors. But we like to give guests a preposterously lavish evening, because they’re the kind of people who wouldn’t turn up for anything less. They fork out small fortunes for new dresses and so on, the sponsors blow hundreds of thousands on creating what convention demands we call a “magical world”, and everyone wears immensely smug “My diamonds are by Chopard” grins in the newspapers and OK. Once we’ve subtracted all these costs, the leftovers go to my foundation. I call this care-o-nomics. As seen by Marina Hyde ”

The judge in the case (Tugendblat J) held that the above words, in their context, were not capable of bearing a defamatory meaning, stating that “it is common ground that the meaning of words, in law as in life, depends upon their context.”

In this case, the words were contained in the Weekend section rather than the news section, and were headed ‘a Peek at the Diary of Sir Elton John’ in circumstances where no reasonable reader could understand them as being written by the Claimant, and where any reasonable reader would regard them as an “attempt at humour”.

Broadsheet: “So the fact that Waterford Whispers is a well known satirical website, known for ironic, non-factual stories, is relevant here?”

LCD: “Highly relevant. Any reasonable jury would have to take into account the story appeared on a website which contains stories like “David Cameron Urges Politicians to Refrain from Raping Children for the Time Being‘, ‘Rome Actually Built in a Day, New Evidence Reveals’ and ‘Child Refused Entry into Restaurant Due to Having D4 Parents‘.”

Broadsheet: “Like calling you a secret tea sipper.”

LCD: [drains ice cold Frappuccino]: “No.”

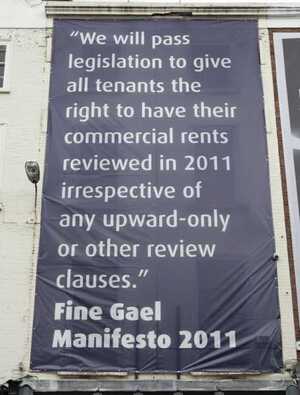

Broadsheet:“They also featured a story entitled ‘Denis O’Brien To Sue Everybody‘.

LCD: “The fact that satire may sometimes turn out to be true does not mean that reasonable people take what is said on a satirical website seriously. It would however allow the publisher of that website to raise the defence of truth along with the argument above. And it would be interesting to see what extent satire would be deemed to be in the public interest. However I think because of the nature of Waterford Whispers’ stories generally, the case falls within the Elton John principle and no defence is necessary.”

Broadsheet: “It’s a serious business this satire.”

LCD: “I’ve just explained that it’s not.”

Broadsheet: “Sorry Legal Coffee Drinker. I was being [suppressed giggle] ironic.”

LCD: *click*

Last night: Meanwhile, In A Parallel Universe

(RollingNews.ie)