From top: Fine Gael Minister for Finance and Public Expenditure and Reform, Paschal Donohoe on his way into talks with Fianna Fáil over the 2019 budget at the Department of Finance last week; Michael Taft

The orthodoxy is running loose, we are being frog-marched into another round of depressed spending and progressives are nowhere to be seen.

Fiscal policy can put a lot of people to sleep, especially as it is presented in numbers, ratios and sometime dubious historical parallels. But it is one of the key foundation stones in the area of public expenditure, investment, taxation and, most of all, macro-economic stability.

Lately we have been treated to a barrage of calls to ‘run a budgetary surplus’, ‘rein in our high debt levels’, ‘prepare for Brexit’ and ‘avoiding over-heating’. Each of these is contestable and has profound implications for social and investment policy. For the most part, the Left is silent and the debate has the sound of one-hand clapping.

We are in danger of a repeating the experience during the austerity period when the orthodoxy set the (narrow) parameters of the debate and the Left failed to develop a common programmatic response. Let’s go through some of these issues (in the next post we’ll discuss the overall debt).

Tainting the Golden Rule

Ministers, the Department of Finance, the Central Bank, the ESRI and the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council are all calling on the government tighten up on spending so as to create a surplus – that is, to ensure that government revenue exceeds government expenditure.

The bases on which they are making these calls, however, are flawed.

Traditionally, the benchmark for fiscal policy is the Golden Rule. This states that over the medium-term, the Government should borrow only to invest and not to fund current – or day-to-day – spending. The rationale behind this is that current spending benefits today’s taxpayers; investment benefits tomorrow’s taxpayers.

Of course, there are ups and downs. During a recession current spending will go up with increased unemployment benefits while tax revenue will fall as business activity declines. When the economy recovers, a prudent Government will run a surplus on current spending to make up for the deficits in the recession; hence, over the medium-term deficits and surpluses balance out.

This was the rationale behind the original Maastricht guidelines – which permitted a three percent deficit. This allowed for borrowing for investment purposes while requiring that current spending was in balance or even in slight surplus.

The Golden Rule was undermined by the Fiscal Rule which stated there must only be a 0.5 percent deficit (one percent for those countries with an overall debt level below 60 percent of GDP).

This means that Governments are not allowed to borrow to invest. They must fund most of investment out of current income.

This is irrational for two reasons:

What would happen if households had to fund major investments out of current income – house purchase, retro-fitting, new car, etc?

Central Bank rules require households to pay 10 percent of the house price (investment) up front. Imagine if those rules required households to pay 70 or 80 percent of the house price: house purchases would collapse along with the building sector.

Why would you not borrow for investment when interest rates are on the floor?

But now it is getting worse. By demanding that the entire budget be in surplus many commentators are going beyond even the restrictive fiscal rules, tuning the Golden Rule into rust.

They are demanding that not only should all investment be paid out of current revenue but that there be an additional large surplus. This is despite our many infrastructural deficits.

How Do We Compare?

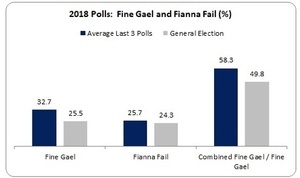

In an attempt to frog-march us into this depressed future all manner of numbers and ratios are used, most of which miss the Golden Rule mark. How does our current budget balance compare to the rest of the Eurozone?

Not only does Ireland have a very high surplus on current, or day-to-day, spending compared to the Eurozone; it is rising much faster. The Government intends to drive this up even higher in 2020 and 2021.

This is not only unnecessary in terms of the fiscal rules; it deprives the productive economy of badly needed resources.

If we enter the next downturn, slump or recession with a housing crisis, an unaffordable and poorly paid childcare system, low levels of R&D and per student expenditure we will find an economy struggling to return to growth.

On the other side of the downturn it will cost even more to repair the economic and social damage, repeating the same mistakes we made coming out of the last recession.

A Progressive Starting Point

What should progressives be proposing? First, we should argue adherence to the Fiscal Rules, that is, a 0.5 percent deficit. This would facilitate economic and social investment.

The Government’s Summer Economic Statement gave us a table showing what additional expenditure – above Government projections – would be allowable under the Fiscal Rules.

Over the next three years we would be allowed to spend over €4.1 billion above what the Government intends. This is a sizeable amount available for investment.

Of course, this doesn’t tell us where to spend the money – that is another debate to be had (for my money it would be housing, childcare, education, R&D and primary healthcare).

Second, progressives should use the European elections to argue, on the basis of a common platform, to exclude investment from the fiscal rules. This would return fiscal policy back to the Golden Rule. The EU Commission has already taken small steps in this direction.

Third, progressives should challenge orthodox assertions regarding debt, deficits, growth, investment and over-heating. Evidence-based arguments should be put forward along with common-sense explanations.

In short, progressives should get back into the debate over fiscal policy – by proposing an alternative medium-term framework.

In doing this, though, progressives should also confront the real dangers that lie ahead – and do so in open and honest manner: Inflated revenue levels due to multi-national accounting practices; rising interest rates – probably starting in 2019; Brexit; a global slowdown due to the next downturn, fueled by tariffs and trade wars, etc.

This is no easy task. The orthodoxy can put forward its arguments based on simplistic and static budgetary arithmetic that overlooks the negative economic and social impacts which ultimately undermines a prudent fiscal policy.

We must argue an alternative framework that promotes investment in the productive economy. For it is the strength of the productive economy that will see us through the troubles ahead – and provide a pathway to sustainable growth and increasing prosperity on the other side.

Michael Taft is a researcher for SIPTU and author of the political economy blog, Notes on the Front.

Interesting reading.

1. If we were to increase our borrowing there would be a risk that the government would ‘waste’ this extra 4 billion on either tax-cuts or public-sector pay increases rather than investment.

2. When you compare Ireland’s ratio of National Debt to GNI* (~100%) versus the rest of the EU – we are in the PIGS. The EU average is 82% Is adding to our debt sensible?

half of which wasn’t ours. debt that is.

Not really.

About a quarter of the national debt is banking-related debt. The other three quarters is over spending.