From top: Pensioner on the Ha’penny Bridge, Dublin; Michael Taft

The pension debate is overly complex and full of scare mongering.

That ends here.

Michael Taft writes:

Get ready for the big upcoming pension debate. Hopefully it won’t be conducted like the ‘we-are-taxed-too-much’ debate or the ‘Irish-wages-are-too-high’-debate.

Hopefully the pension debate will be evidence-based, without unsubstantiated assertions or slogans masquerading as policy. Let’s keep hope alive by looking at a couple of issues arising out of the report from the Interdepartmental Group on Fuller Working Lives.

For many, pensions are as exciting as a snail race. But believe me, when you get to a certain age it becomes seriously interesting. And with the rising number of elderly, it will become even more prominent in the debate.

The Interdepartmental report focused on the specific dilemma facing people forced to retire at the age of 65 but not being eligible for a pension until they turn 66 (by 2028 the eligibility age will be increased to 68). But the report touches upon wider issues. Let’s look at two of them.

We Can’t Afford Them

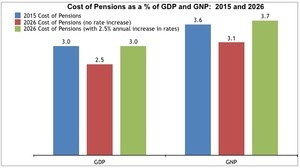

We’re going to get a lot of ‘we-can’t-afford-them’ – that is, future pension costs will be fiscally unsustainable due to the rising number of pensioners: .

‘Expenditure on State Pension payments and relevant supplementary payments is estimated to rise from just over €6.5bn in 2015 to around €8.7bn in 2026, assuming no further changes in rates – an increase of 34%.’

While they don’t scare-monger these numbers, others will. But should we be overly-worried about this number?

As a proportion of national output (GDP or GNP) these numbers indicate that pensions will actually cost less in the future; at least up to 2026.

Using the report’s own numbers, pensions as measured as a proportion of national output will fall between 2015 and 2026 – whether measured by GDP or GNP. In my own calculations,

inserting a 2.5 percent annual increase in weekly pension payments, the cost remains the same. This doesn’t factor in the increased revenue – higher income and indirect tax revenue which will offset a small part of the cost.

Yes, there is a problem with GDP and GNP measurements, but the above measure trends. After 2021 I assume a 4 percent nominal increase in GDP and a 3.5 percent nominal increase in GNP).

This is not to under-estimate the challenges of funding people’s post-retirement income; after 2026 the cost will continue to rise. But it is important to keep these rising costs in perspective.

There’s Going to Be More of Them

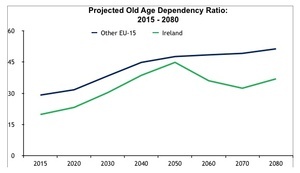

More pensioners, that is. Which brings us to another issue – the age-dependency ratio. It has been pointed out that there will be fewer people at work supporting more people retired – a real social, economic and fiscal challenge.

Ireland’s dependency ratio, while staying below the mean average of other EU-15 countries, will nonetheless double over the period to 2050 – to 45 percent. After that the ratio falls to the level that exists in other EU-15 average today – and then rises again.

A couple of things to note about this type of projections. First, it is highly sensitive to small changes in variables such as immigration levels, longevity, fertility, etc.

To show how fragile these projections can be, just remember Ireland in 1989. High emigration, low immigration; who would have imagined that within 10 years everything would be turned upside down. If it’s hard to project demographics over a decade, try attempting it over multiple decades.

Second, age and pension-dependency ratios are also a product of policy. For instance, even under same variables, the above chart is out-of-date. The age range is 65. But Irish policy is to increase the pension age to 68 by 2028. This will improve the dependency ratio under current projections.

Or how about this: the Government pledged to take in 4,000 Syrian refugees yet only 350 have arrived. If we were to have a more pro-active immigration policy, we could improve the dependency ratio.

Why do you think Germany committed to taking so many in? Under current projections, their dependency ratio will rise to a staggering 60 percent, with the population in decline (many EU countries are facing into falling populations).

That’s why what’s called the European ‘immigration crisis’ is actually a ‘social and economic opportunity’.

Again, this doesn’t under-estimate the challenge but hopefully it will point us to positive proposals, rather than an alarmist debate.

Just Outlaw It

The purpose of the inter-governmental report was to address the issue of raising the pension age while people were still required to retire at 65 years. The report calls for a number of interventions, mostly aspirational.

Why not just forbid forced retirement at the age of 65. Retirement should at least become mandatory only when someone is eligible for a state pension.

Or why not go further and just outlaw age-ism. People should be given a range of work-choices – continuing to work past the pension age, reduce working hours, or retire at the pension age. If someone is not considered fit to continue working in a company, it should be treated as a health and safety issue, not an issue of an arbitrary age.

There is no denying the complexity of the issues regarding ageing, pensions, life-time savings and the diminishing number of defined-benefit occupational schemes. We will need an informed debate based on evidence with proposals that are intended to enhance peoples’ life-options and living standards.

One might be pessimistic that this will happen when one considers the how debates over tax, spending cuts, competitiveness, etc. have been, and continue to be, conducted.

But one should live in hope – hopefully for a long, healthy and prosperous life-time.

Michael Taft is Research Officer with Unite the Union. His column appears here every Tuesday. He is author of the political economy blog, Unite’s Notes on the Front. Follow Michael on Twitter: @notesonthefront

I agree with Mr Taft.

I must lie down now.

there there, it’ll be all right.

A few more angles on this.

When referring to pensions above, Mr. Taft is mainly discussing the cost of state pensions. Other states such as Singapore, Australia & UK have tackled the problem by having soft compulsory private pensions as well.

One of the big elephants not discussed is the cost of private pensions. There’s always complaints that we’re not putting enough in but very little discussion on what is taken out in fees & charges.

The most effective long term investment is index trackers, not managed funds but Irish pension companies do not provide them. Irish pensions are among the worst performing in Europe.

If incomes are low or stagnant, its very difficult for people to plan long term if immediate needs are under constant strain. People are struggling now who have savings locked up for decades. Need to have an emergency release mechanism.

If we cannot encourage our own young people to stay in this country, to be able to afford a roof over their heads, decent living & working conditions, then the dependency ratio will get worse.

Too often over the past few years, we have seen older people pull up the ladder behind them in order to protect their own incomes without regard for the needs of younger generation.

I am confused on your last point about older people pulling up the ladder behind them. My own experience shows older people tapping into their own nest eggs to help their younger family members get their foot on the ladder. Parents offering to have their adult children & grandchildren stay at the family home, helping with child-care, providing financial aid etc. It’s what most parents & grandparents that I know do. Your last point suggests something different. Can you elaborate please ?

Individual family members are helping each other as best they can but not everyone is in a position to give adult children money for housing deposits.

But in state policies, young adults 18-35 have borne the brunt of emigration, reduced state starting salaries, rent / housing problems, unstable employment and resultant stree related mental health problems. Older people in more stable circumstances have been largely able to maintain what they have built up.

Background:

http://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/recession-hit-hardest-at-generation-now-in-20s-and-mid-30s-1.2596961

http://www.thejournal.ie/esri-report-great-recession-1919516-Feb2015/

You may find that many of the older people you refer to are former emigrants themselves. They would have emigrated back in the 50’s, 60’s, 70’s & ’80’s in much tougher conditions than we have today. Many of those that returned home, did so for family reasons. They would have taken a financial hit in returning home, but it’s not all about the money. Using other metrics, Life is pretty good here in Ireland.

Just because we have a history of driving out young people, doesn’t not mean it has to continue.

For some sections of Irish society, yes it can be pretty good. But for too many, its far from it.

For those of us without a job, the Irish welfare system is pretty generous, compared to other countries. If you ask many Emigrants why they left, it’s not because they were driven out. Many of them left by choice – because they wanted to explore & expand their horizons. To those still not happy with the situation here in Ireland, I would suggest plucking up the courage to leave. In doing so, I bet they would soon realize that things are not so bad at home.

Good grief – if you don’t like it, leave?

How about if you don’t like it, stick around and get involved in civic action to make the changes you want to see be it politics, pressure group, union whatever takes your fancy.

That attitude is precisely what is wrong.

Many people who leave already have jobs. Working people are not getting enough reward for their work here. Decent jobs, decent wages, decent homes, decent life should be the norm.

We are already contributing to our state pension throughout our working lives. Its called PRSI. If this was managed efficiently there would be enough for everybody.

PRSI goes to pay those who are currently pensioners, its not invested to provide for your own pension.

The national pension reserve fund was set up to deal with the states own employees, it wasn’t a general pension fund. Unsure if its exists after the resession.

It’s definitely been tapped more time than Michael Flatley’s shoes.

Every effort must be made to ensure Bertie Ahern ‘s 10,000 monthly pension is maintained. This is a priority.

Your state contributory pension is a function of how long you work (but not how much you earn) and 3 other things:

-performance of Irish economy a very long time in the future

-willingness of society to fund older people

-how many OTHER old people there are in Ireland at the time

As Michael points out all of these things are INCREDIBLY uncertain. In my view we should be buying insurance against it by putting a large chunk of PRSI (€3BN a year even) into a fund or funds with low costs and an investment strategy designed to be as UNCORRELATED to Irish economic performance as possible.

Second, private pension funds are a mess. The tax relief allows the rich to overbenefit, fees and charges destroy return before it’s ever made and the whole industry is inefficient (ditto insurance btw). Citizens should have the opportunity to top up their account described in the previous bullet.

Finally, public service pensions have had their long-term costs reduced a lot in recent years but DB pensions of any sort are absurd in this era and should go.